Testing Strategy

Comprehensive overview of our testing approach and methodologies

Overview

Our testing strategy follows a comprehensive approach that includes various testing levels and methodologies to ensure the quality and reliability of ReadingStar.

An iterative testing approach was utilised across the development of the project. While most use cases are quite intuitive, we ensured to cover the breadth of possibilities that our program could face, in everything from vocal input to the hidden API calls.

Testing Phases

There were three main phases of testing:

- Unit and performance testing: Does the application do what it is expected to do, and in a reasonable time?

- Integration testing: Do different components of the application cooperate with each other effectively and efficiently?

- User acceptance testing: Is the application’s user experience (UX) satisfactory for the context of the user and the action being performed?

Unit & Integration Testing

Detailed testing of individual components and their performance metrics

Unit Testing

To test performance of the application, we looked at whether individual units were executing as expected, and analysed the real metrics of the application functions, through speed and resource use.

Integration testing was included with these API calls, such as playlist management functions, as React Native Windows does not inherently possess capabilities for UI tests.

We began unit testing with PyTest for all endpoints of the backend API in the file api_test.py. They were performed with the instruction python -m unittest api_test.py.

API unit testing

| ID | Test case | Assertions | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Final score generation from a .WAV recording, with a mocked OpenVINO pipeline | Score response OK’d (code 200) Key ‘final_score’ present in the API response JSON final_score ≈ 0.85 |

Pass |

| 2 | Getting playlists from the JSON | Get request OK’d Key ‘playlists’ present in the API response JSON |

Pass |

| 3 | Updating playlist | Post request OK’d Key ‘message’ = ‘update completed.’ New song in the playlist JSON |

Pass |

| 4 | Remove a song from the playlist | Post request OK’d Key ‘message’ = ‘remove completed.’ Song no longer present in playlist JSON |

Pass |

| 5 | Delete a playlist | Post request OK’d Key ‘message’ = ‘remove completed.’ Playlist no longer present in JSON |

Pass |

| 6 | Updating live lyric | Post request OK’d Key ‘message’ present The new lyric present in JSON |

Pass |

| 7 | Sending full lyrics to app | Post request OK’d Confirmation of lyrics receipt |

Pass |

| 8 | Getting the live match score | Get request OK’d Similarity = 0.6 No lyric match (test threshold is 0.7) |

Pass |

| 9 | Microphone switch-off | Get request OK’d Confirmation of microphone switch-off |

Pass |

| 10 | Embedding_similarity_ov function | Tokenizer result ≈ 0.9 Tokenizer was called just once Model was called just once Normalizer was called just once Cosine was called just once |

Pass |

Compiling

Compilation and build testing of the application

Overview

As mentioned previously, our app uses a Python back-end and React Native Windows front-end. In the back-end, model inference is performed using the AI models which we converted to OpenVINO (Intermediate Representation) format before compiling. The models were downloaded from Hugging Face. Meanwhile, the back-end is accessed using FastAPI endpoints, to which the front-end submits GET and POST requests.

Compiling the full stack

We first employed PyInstaller to compile the Python back-end file into an executable. As OpenVINO pipelines are written in C++, there is no cost to performance as the pipeline code is the same in both versions.

Next, we created an .MSIX installer for the React Native app front-end. However, due to MSIX sandboxing, one issue that arose when downloading ReadingStar through it was the app’s inability to access localhost. This meant that the front-end and back-end could not communicate with each other, as signals from the API would not be picked up. To overcome this, we identified the family package name of the application and created a command which gave ReadingStar loopback capabilities.

Packaging the app

Finally, to package the project, we wrote an installer batch file which installs the MSIX and runs the loopback command. Then we wrote a launch batch file which initiates the back-end, then the front-end, to ensure that the MSIX front-end is able to connect with the back-end API and make requests after installation.

To test, we ran this installer on multiple different Windows PCs. It successfully ran and installed on all devices, and the application behaved as expected in all use cases.

Performance Testing

Power usage testing and performance optimization results

Performance Testing and Analysis

Base performance testing

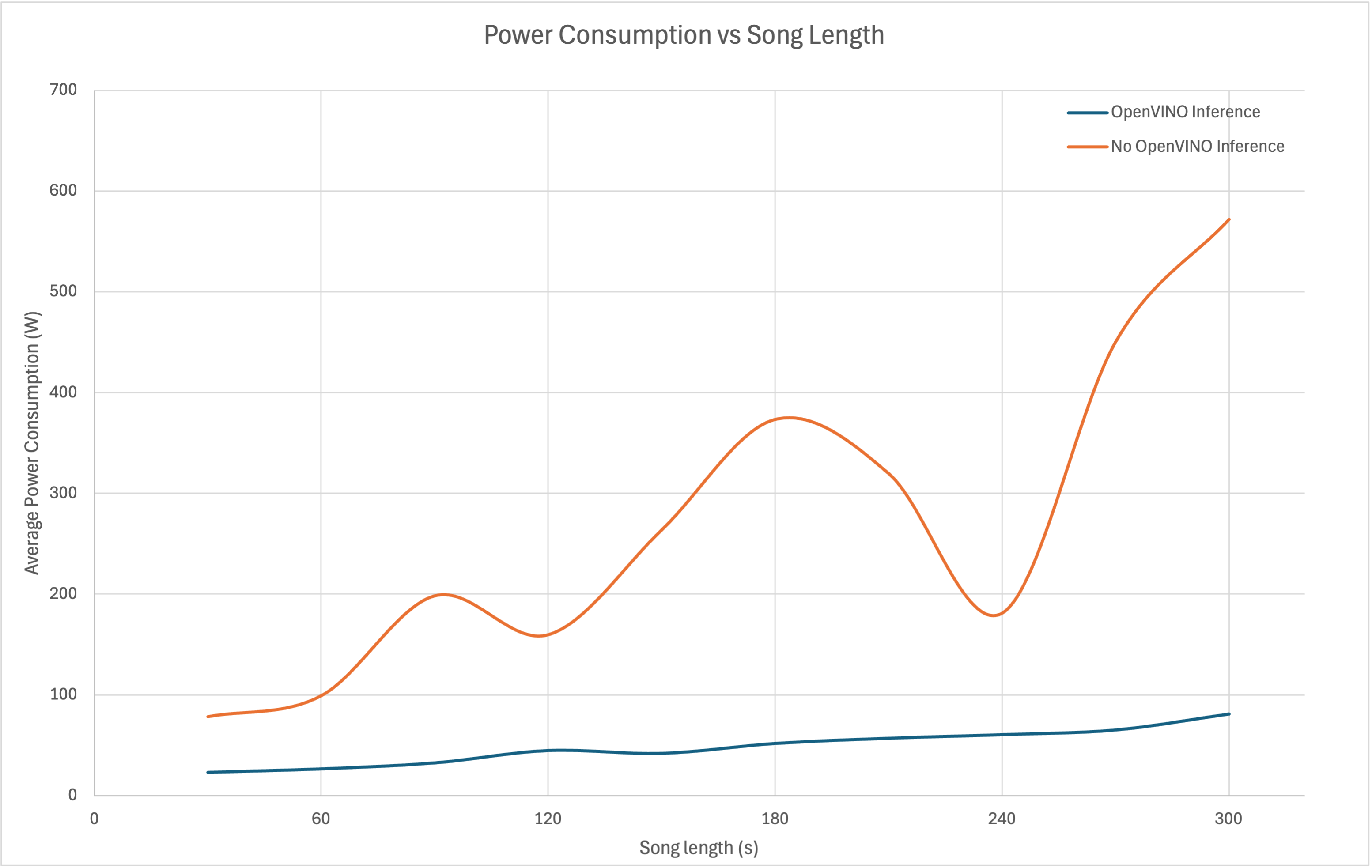

We analysed the inference time of the Whisper model on 500 .WAV tracks, with length between 30 seconds and 5 minutes, with and without Intel’s OpenVINO inference pipeline, on an average Windows laptop CPU.

The CPU specs:

- Intel Core i5-12450H

- 16GB RAM

- 8 cores, 2.00 GHz clock speed

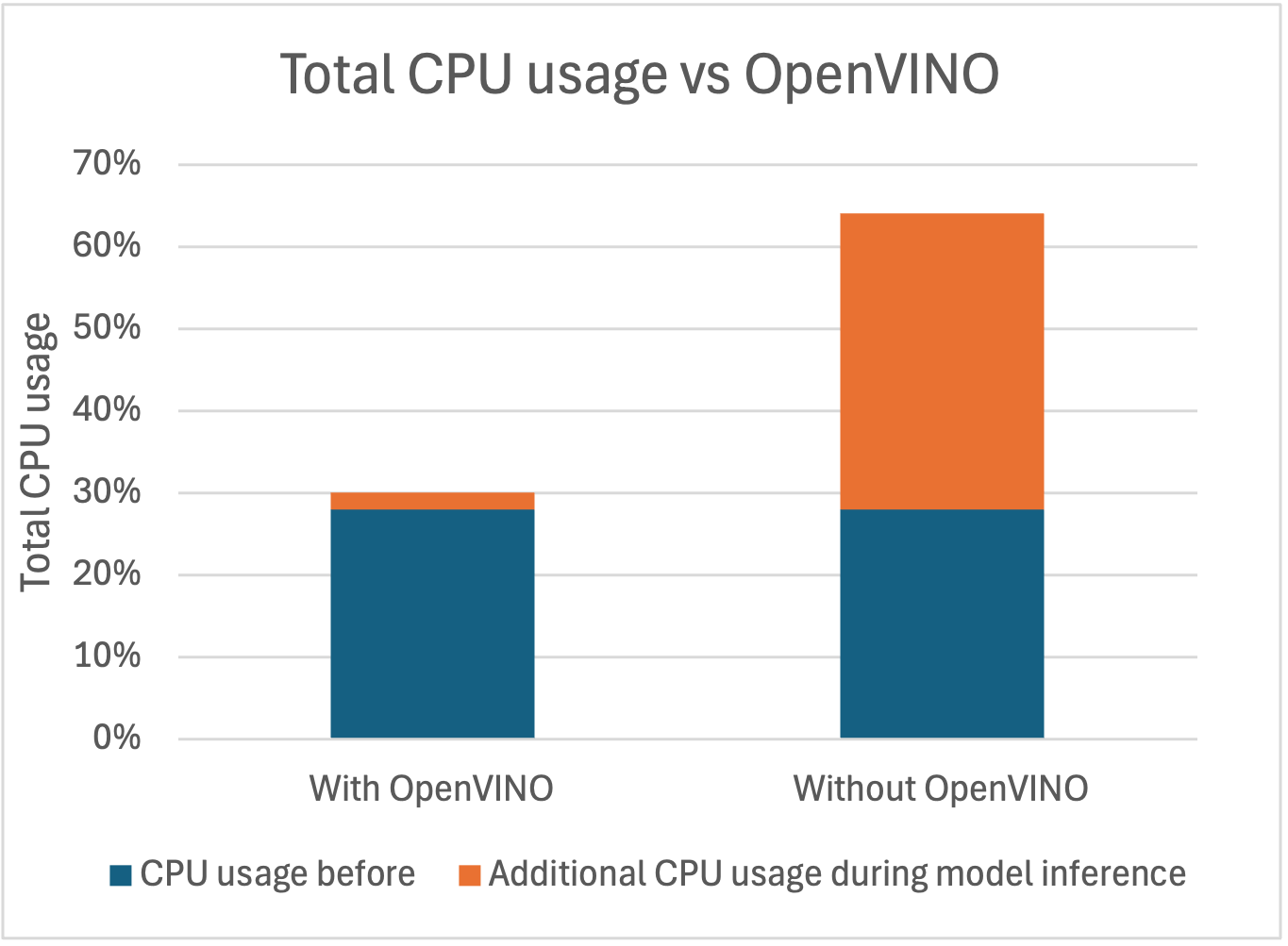

Note: the CPU usage before the model was run in either case sat at overheads of ~28%.

As shown by the first figure, without the OpenVINO pipeline, performance is deprecated, because there is nothing to optimise the Whisper model when transcription. This would make its use without the pipeline intractable for the speeds required for near-instant feedback.

Furthermore, analysis of power usage in complete inference, from the second figure, further asserts how crucial OpenVINO is for exceptional performance in ReadingStar. On average, it uses 5.5x less energy while producing output in the exact same time as a non-OpenVINO model.

Hardware testing

For hardware testing, we compared the performance of ReadingStar on a range of devices to understand how the application behaves on different hardware configurations.

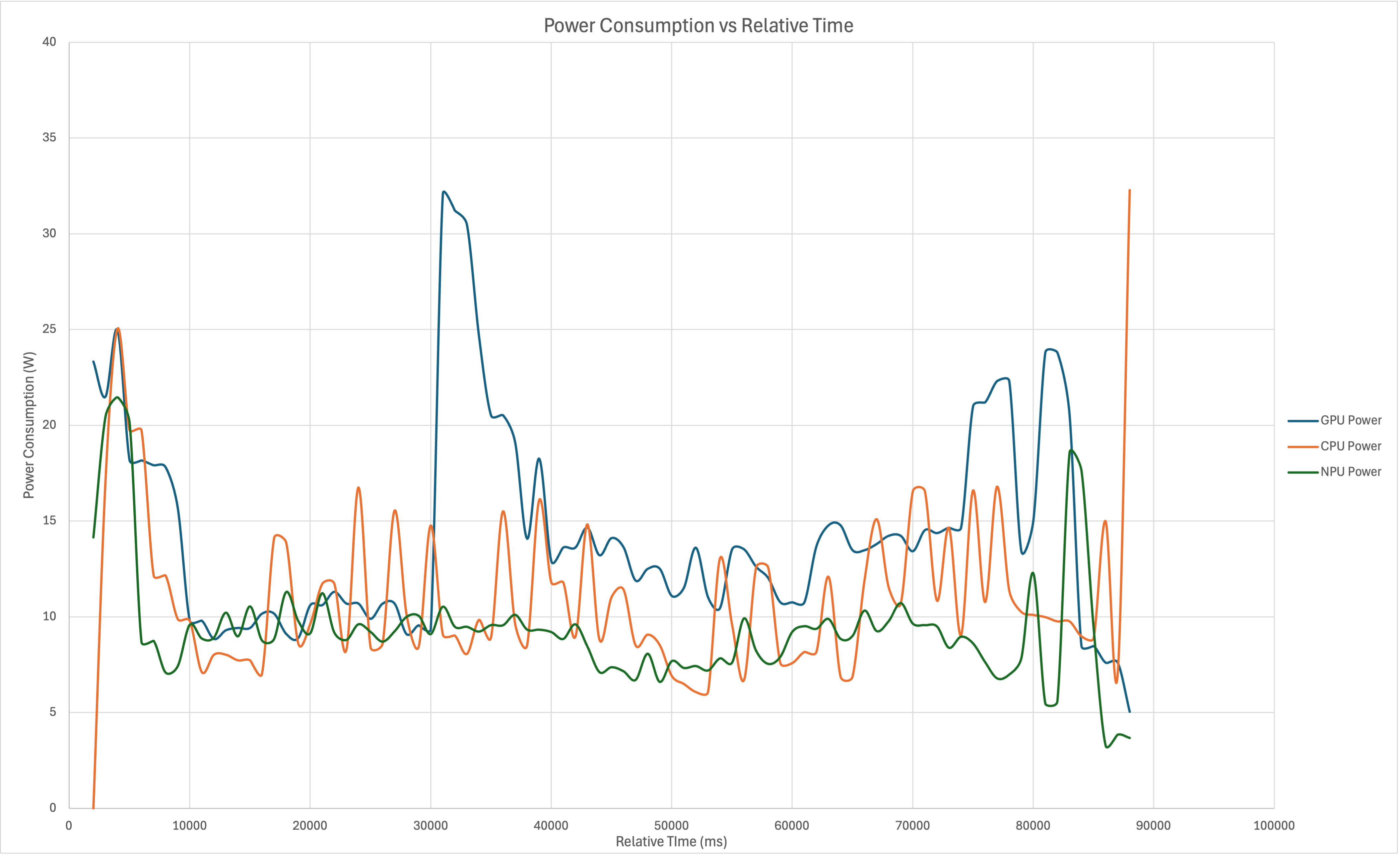

The OpenVINO pipeline can optimise AI processes on either the native CPU, GPU, or, if available, the NPU (neural processing unit). We tested OpenVINO on the Intel® Core™ Ultra 5 Processor 125H, which contains three devices:

- Intel Core Ultra 5 Processor 125H CPU (14-core, 4.50 GHz)

- Intel Arc Graphics GPU

- Intel AI Boost NPU

The following graph illustrates the total package power consumption when using different inference devices over a complete session in the ReadingStar application. In all cases, the majority of the power consumption is done by the CPU, as it is responsible for running the application. The key difference lies in the additional power consumed during inference, depending on the device used.

Comparing the CPU and NPU utilised graphs, the peaks of package power are considerably higher when not utilising the NPU; the maximum power consumption when utilising CPU is 32.28 W in comparison to 21.46 W when using the NPU for inference. Additionally, the power consumption when utilising CPU for inference is much more erratic, this is because during batches of live transcription, the computer is using CPU for automatic speech recognition inference, which leads to frequent fluctuations in power usage. These fluctuations are still visible when using the NPU for the batch inference, but as the NPU is much more efficient for AI inference, the variations are much smaller and more stable.

As for the GPU graph, its power consumption shows even greater fluctuations than the CPU. This is expected, as GPUs are designed for training rather than inference, making their power consumption highly variable when carrying out the batch inference in the application session. The GPU has a max of 32.07W, similar to CPU, but the batch inference fluctuations are unstable and less consistent as the GPU attempts to optimise through parallel processing and high-throughput workloads.

Overall Energy Impact

The song used for testing power consumption is “Humpty Dumpty” by Super Simple Songs, and has a length of 1 minute, 19 seconds.

Taking Energy (Wh) = Power (W) × Time (h) and assuming a battery capacity of 50Wh as standard for most standard-spec 2020s laptops, we can subsequently use the formula for energy to estimate the battery life savings as a result of NPU-efficient inference when running the ReadingStar app:

| Processing Unit | Power Consumption (W) | Energy per Song (Wh/song) | Songs per Full Laptop Battery Charge | Estimated Battery Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intel Core Ultra 5 Processor 125H CPU | 11.10 W | 0.244 Wh/song | 205 songs | 4.5 hours |

| Intel Arc Graphics GPU | 14.42 W | 0.316 Wh/song | 158 songs | 3.5 hours |

| Intel AI Boost NPU | 9.33 W | 0.205 Wh/song | 244 songs | 5.4 hours |

This gives approximately 20% extended battery life when running Reading Star with an NPU for inference over a CPU and a 54% extended battery life over a GPU.

In conclusion, using a device with an NPU when running AI-powered applications like Reading Star leads to significant battery life and efficiency improvements at no additional cost to speed, totaling to almost an extra hour of playtime in our tests over a CPU, and 2 hours over a GPU.

User Acceptance Testing

Results from user testing sessions and feedback

Usability testing was informally performed throughout the project, but as always, the experience and feedback from external users proved invaluable. With this, our main goals as a team were to:

- Learn how well the application executes outside of a control environment, i.e. quiet room with a strong microphone.

- Observe how users of differing demographics interact with the program.

- Discover previously unknown faults or execution errors.

- Understand if the experience using the application is enjoyable!

The following tests included a wide range of actions, from the benevolent user singing the first song in the playlist, to the most rigorous of testers trying to break it!

Our first usability tests were performed by sixth form students, who were impressed by its intuitive flow, and were intrigued by the rewards system.

We then took our program to the Helen Allison School, based in Meopham, Kent.

| Individual(s) | Feedback | Adjustments made (if any) |

|---|---|---|

| Class of 12-year-olds | “Children enjoyed singing along with songs they are familiar with” | Playlist creator feature |

| Teacher of 12-year-old class | “Visuals for songs” “Colours for words” “Could 2 singers compete against each other?” Progress bar added underneath text, in time with lyric |

Progress bar added underneath text, in time with lyric |

| Pupil (8-year-old) | “Love music [selection], it was loud” | N/A |

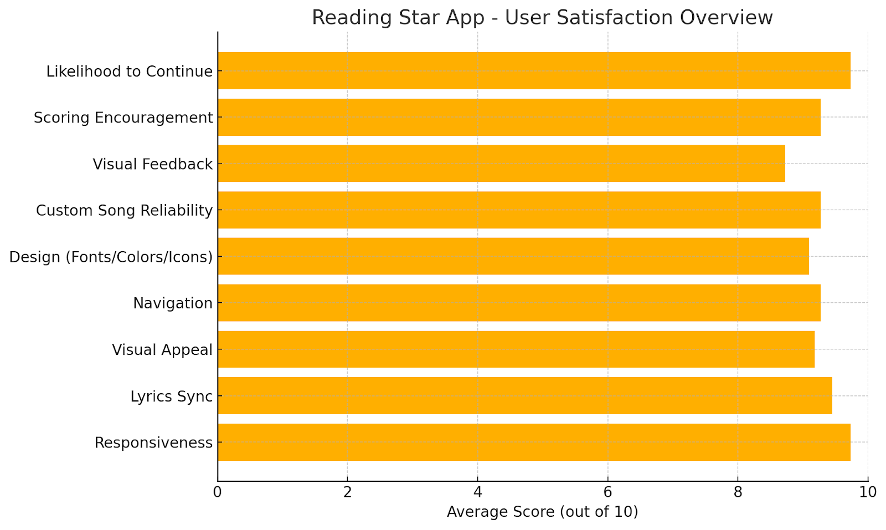

ReadingStar User Survey Analysis

The recent user survey for Reading Star reveals highly positive feedback across all categories. Users rated the app's responsiveness, design, and usability between 9 and 10 on average, with the overall experience scoring exceptionally well. The app’s interface was praised for being clean, intuitive, and visually appealing, while core features like karaoke and scoring systems were highlighted as fun and engaging.

Some users suggested improvements, including adding tutorials, a scoreboard, more dynamic UI elements, and access to copyrighted music. Visual feedback received slightly lower scores, indicating an area for enhancement. On the whole though, users found the app enjoyable, encouraging, and worth continued use.