Gesture Recorder

The ability to recognise and classify gestures has been a long-standing challenge within the field of computer vision. Many solutions have been developed using machine learning, an approach which results in a great degree of accuracy but with the cost of requiring large amounts of training data, most of which needs to be labelled manually. This also introduces a time cost for the training process itself, meaning that the average user cannot be expected to record their own gestures.

We are also limited to RGB video data, most commonly from a webcam. This means our algorithms should work on low-resolution video feeds and run efficiently enough to process data in real time on low-end machines. An added challenge we face is that we do not have depth sensors to give us data in 3D.

Approach

The simplest way to break down the process needed is as follows:

- Isolate the gesture from a video

- Decompose the gesture into data

- Record the user performing a motion

- Compare the data to see if it matches

Each of these steps require a separate series of algorithms. Counter intuitively, however, our first challenge would be the last step – to find a way to compare data accurately. From this, we could work backwards and decide how we should extract our data.

Body Detection

Work has been done in the field of gesture classification on RGB videos (Schneider et al., 2019). We build upon this work by refining their method.

The first step is to determine the body in the video to isolate the body landmarks. To do this, we use the MediaPipe library, which can take a video feed and return the coordinates of 33 landmarks. It offers two variations of these coordinates:

- (x, y, z): Normalized to the width and height of the camera dimensions.

- (x, y, z): Real-world 3D coordinates in meters with the origin at the centre between hips.

Although MediaPipe offers a prediction of depth, we did not find it accurate enough to be dependent on and hence we restrict ourselves to the 2D RGB video.

However, we opt to take the real-world data. Although depth may be inaccurate, the x and y axes are consistent within the same scale. We later perform our own normalization pass, so we prefer to keep the raw data.

An optimisation we make is to ignore the landmarks detected on the face, as these are not significant in the process of a full-body gesture.

Extracting Gesture Data

To detect gestures, we must first have a gesture to detect. Once we have a library of gestures, each can be compared against to find the closest matching gesture. Hence, we must first train the algorithm on a gesture.

We prepare a sample video of someone performing a gesture. Just one video is sufficient, as this will determine the “ground-truth” of the gesture. Everything being detected will be calculated relative to the gesture trained from this video.

We construct the 2-by-\(n\) matrix, where \(n\) is the number of frames of the video. A matrix is made per landmark, representing the motion of it through space.

This can be written as \( M = (m_1, m_2, ... , m_n) \) where \(m_n\) is the \((x, y)\) coordinate of a landmark at frame \(n\).

We then preform feature scaling to zero-mean by subtracting the mean of the matrix from it:

$$ M_{scaled} = M - \mu $$

This transforms the matrix to be centred around (0, 0) with a range of [-1, 1]. However, to ensure that all landmarks are relative to each other, we scale the coordinates again by the max axis length of any \(M\)

$$ M' = \frac{M_{scaled}}{max(L)} \: \text{where} \: L = \Bigl\{ max(l) - min(l) \: \lvert \: l \in \bigcup\nolimits_n M_n \Bigl\} $$

Signal Filtering

As suggested by the works of Schneider et al., we apply a moving median filter with a window size of 3 to filter out peaks in the landmark graphs caused by noise or loss in tracking. The code can be seen below:

def median_filter(tracking_points: np.ndarray):

"""Smooth the tracking points using the mean of each point and its neighbors"""

smoothed_points = np.zeros(tracking_points.shape)

smoothed_points[1:-1] = (tracking_points[:-2] + tracking_points[1:-1] + \

tracking_points[2:]) / 3

smoothed_points[0] = (tracking_points[0] + tracking_points[1]) / 2

smoothed_points[-1] = (tracking_points[-1] + tracking_points[-2]) / 2

return smoothed_points

This filter is only applied during the signal filtering step and the median-filtered points are not used later, to preserve peaks in amplitude that may be important for a gesture. We then find the signals with a variance above a certain threshold (we used 0.02 - a value we found experimentally to be suitable) to restrict our tracking to only the relevant landmarks that compose a gesture.

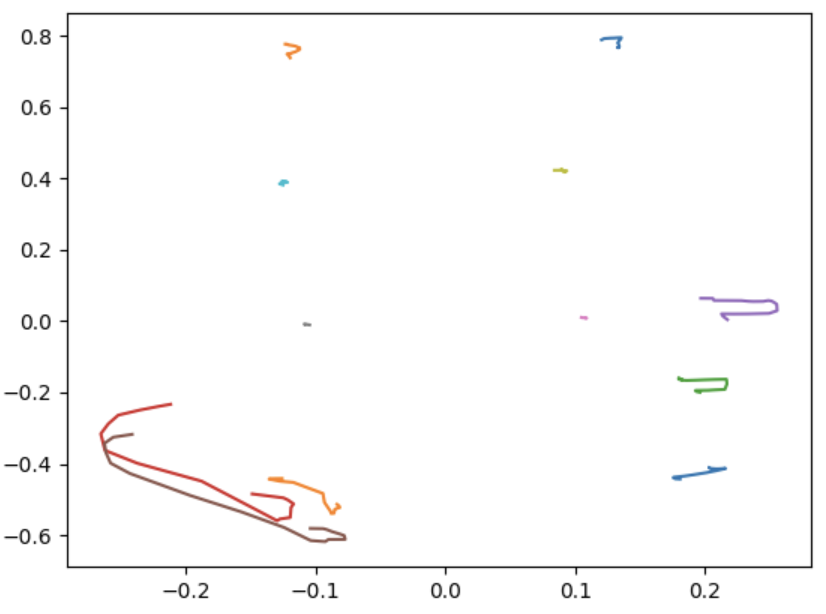

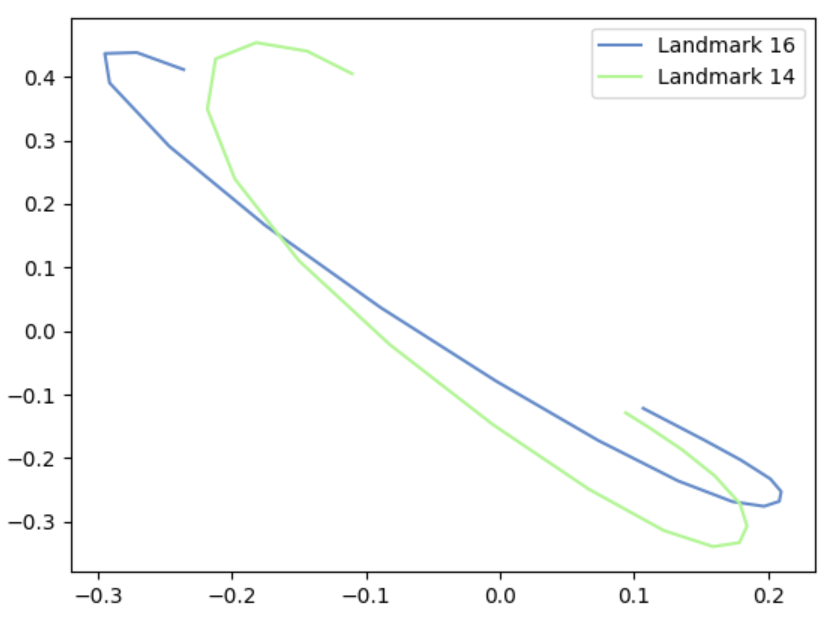

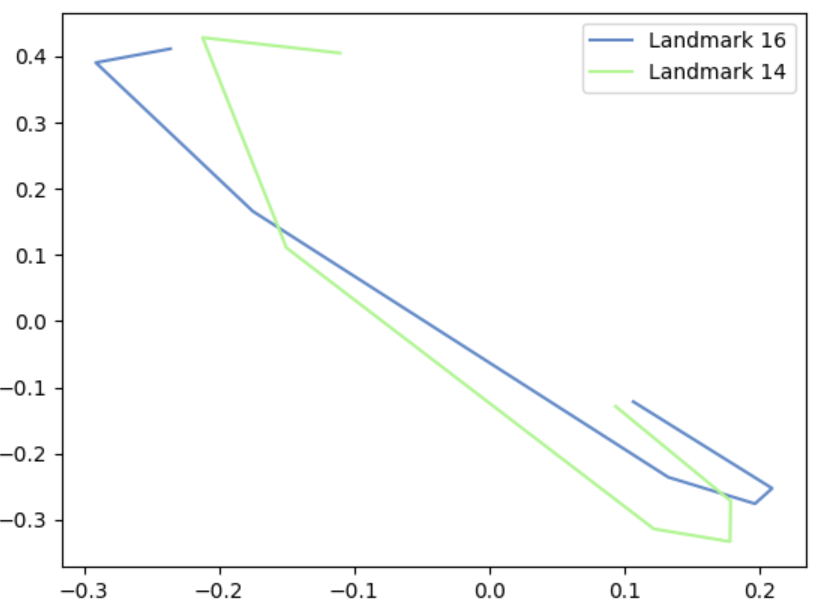

For example, the “punch” gesture has a signal that originally looks like this:

Once we apply feature scaling, it looks like this:

Signal filtering reduces it to two landmarks – the wrist and shoulder:

Smoothing

Although the moving-median filter does a good job of smoothing the signals, we aim to preserve the nature about peaks and valleys, as these are often crucial aspects of a gesture. Hence, we go back to the normalized data and perform a separate series of transformations.

Using a Gaussian filter, we first perform a smoothing step to break the signals down into something that can be reduced simpler, whilst preserving the overall shape. We do this by first computing the Gaussian kernel:

$$ e^{-\frac{(x_i - x)^{2}}{2\sigma^{2}}} $$

We then normalize the kernel by dividing by the sum of it, and return the original signals convolved as according to the kernel. We use an aggressive sigma value of 2.0 and side length of 7 to account for the complexity reduction needed to keep the gesture accessible for those who may not be able to precisely replicate it.

def gaussian_filter(points: np.ndarray, sigma: float = 2.0):

"""Apply a Gaussian filter to the given points"""

# Compute the Gaussian kernel

kernel = np.exp(-np.arange(-3, 4) ** 2 / (2 * sigma ** 2))

kernel = kernel / np.sum(kernel)

# Apply the filter to the points

x_values, y_values = points.T

x_values = np.convolve(x_values, kernel, mode='same')

y_values = np.convolve(y_values, kernel, mode='same')

return np.column_stack((x_values, y_values))

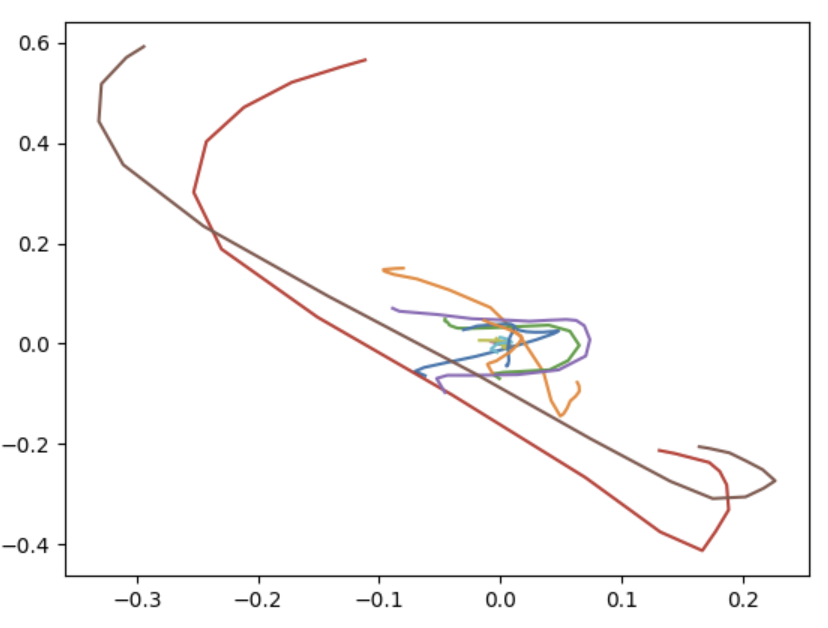

Punch gesture after Gaussian smoothing

Reduction

For the final step, we aim to simplify the coordinates to reduce the array sizes needed to store the gesture in the final JSON file. A Savitzky-Golay filter is applied, where moving sections of the graphs are approximated to polynomial equations, giving an accurate representation of the overall signal whilst smoothing and reducing the points.

def savgol_filter_points(points: np.ndarray, window_length: int, polyorder: int):

"""Apply a Savitzky-Golay filter to the given points"""

x_values, y_values = points.T

x_values = savgol_filter(x_values, window_length, polyorder, mode='nearest')

y_values = savgol_filter(y_values, window_length, polyorder, mode='nearest')

return np.column_stack((x_values, y_values))

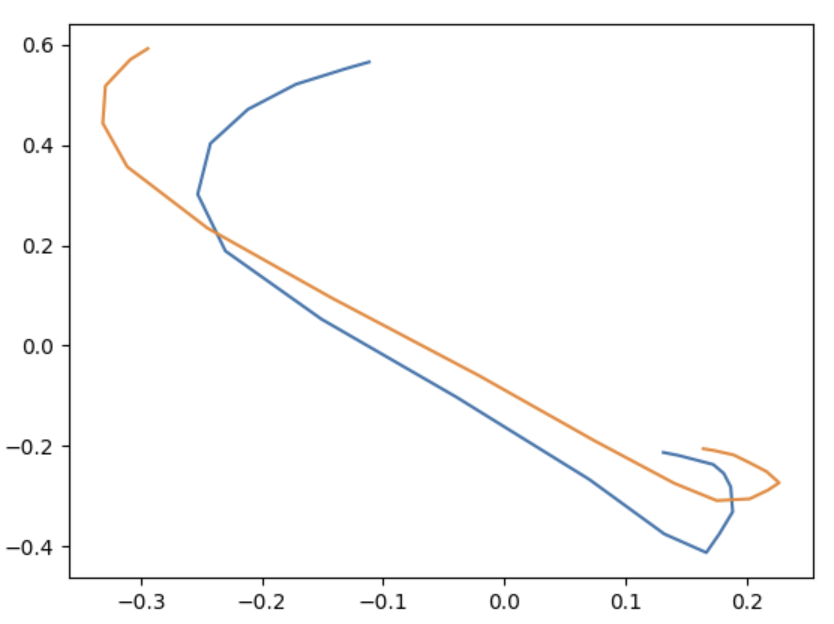

Punch gesture after Savitzky-Golay filter

To reduce the final array sizes, we then use the Ramer-Douglas-Peucker algorithm to reduce the coordinates as much as possible without losing too much data. The algorithm recursively divides the line, finding the midpoints that have the greatest distance from any point, whilst being bound by the end points. If this value is within epsilon, the point is kept.

def simplify_gesture(points: np.ndarray, tolerance: float, start=None, end=None):

"""Simplify the given set of points using the Ramer-Douglas-Peucker algorithm"""

if start is None:

start = 0

if end is None:

end = len(points) - 1

if end <= start + 1:

return points[start:end]

d_max = 0

index = start

for i in range(start + 1, end):

denom = np.linalg.norm(points[end] - points[start])

if denom == 0:

d = 0

else:

d = (np.abs(np.cross(points[end] - points[start], points[i] - \

points[start])) / denom)

if d > d_max:

index = i

d_max = d

if d_max > tolerance:

res1 = simplify_gesture(points, tolerance, start, index)

res2 = simplify_gesture(points, tolerance, index, end)

return np.concatenate((res1[:-1], res2))

else:

return np.array([points[start], points[end]])

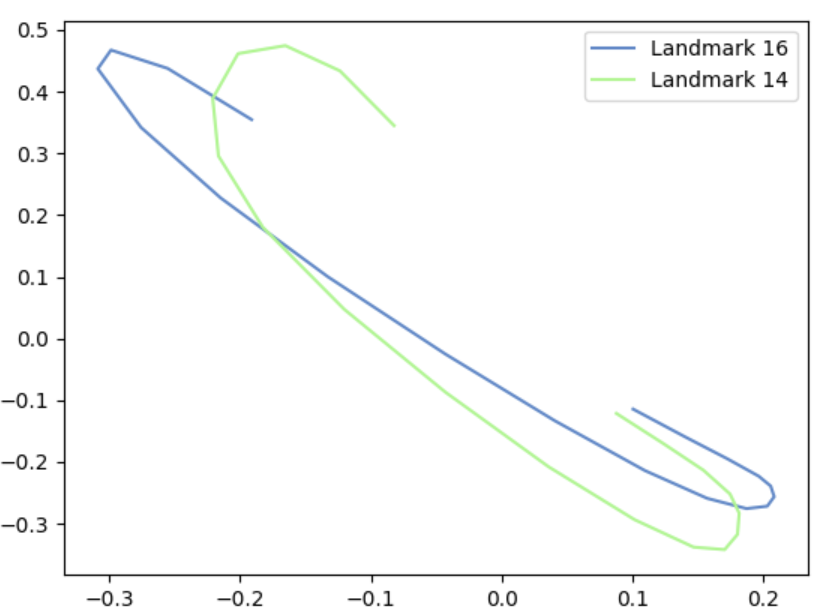

Punch gesture after Ramer-Douglas-Peucker reduction

This not only serves as a compression step, but also means that subsequent detections of the gesture can be a bit more lenient, as exact curves do not need to be followed. This decision was made to ensure that, like previously mentioned, the gestures can be triggered by a range of people making similar, but not necessarily exact, replications of the movements.

The final JSON will look something like this:

{

"16": [

[

-0.23593216121935873,

0.4114285525200301

],

[

-0.29122764690827413,

0.39050805933070437

],

[

-0.1749886776941411,

0.16612659402369012

],

[

0.13273842376899053,

-0.23562188590099653

],

[

0.19699474576552184,

-0.27565540981220144

],

[

0.20972398885153526,

-0.25244847361058836

],

[

0.10685148591740964,

-0.12154869941773049

]

],

"14": [

[

-0.11034779593211581,

0.40496086124592134

],

[

-0.21215575408096204,

0.4283078708572851

],

[

-0.15002866406749532,

0.11082938179054341

],

[

0.12209288057901993,

-0.313689028784506

],

[

0.17850962975715,

-0.33288743103839985

],

[

0.17895087203347146,

-0.2715065003010426

],

[

0.09376114198806573,

-0.1286408402784482

]

]

}

This reduced array size also means reduced runtime complexity, allowing us to handle real-time gesture detection with minimal latency.

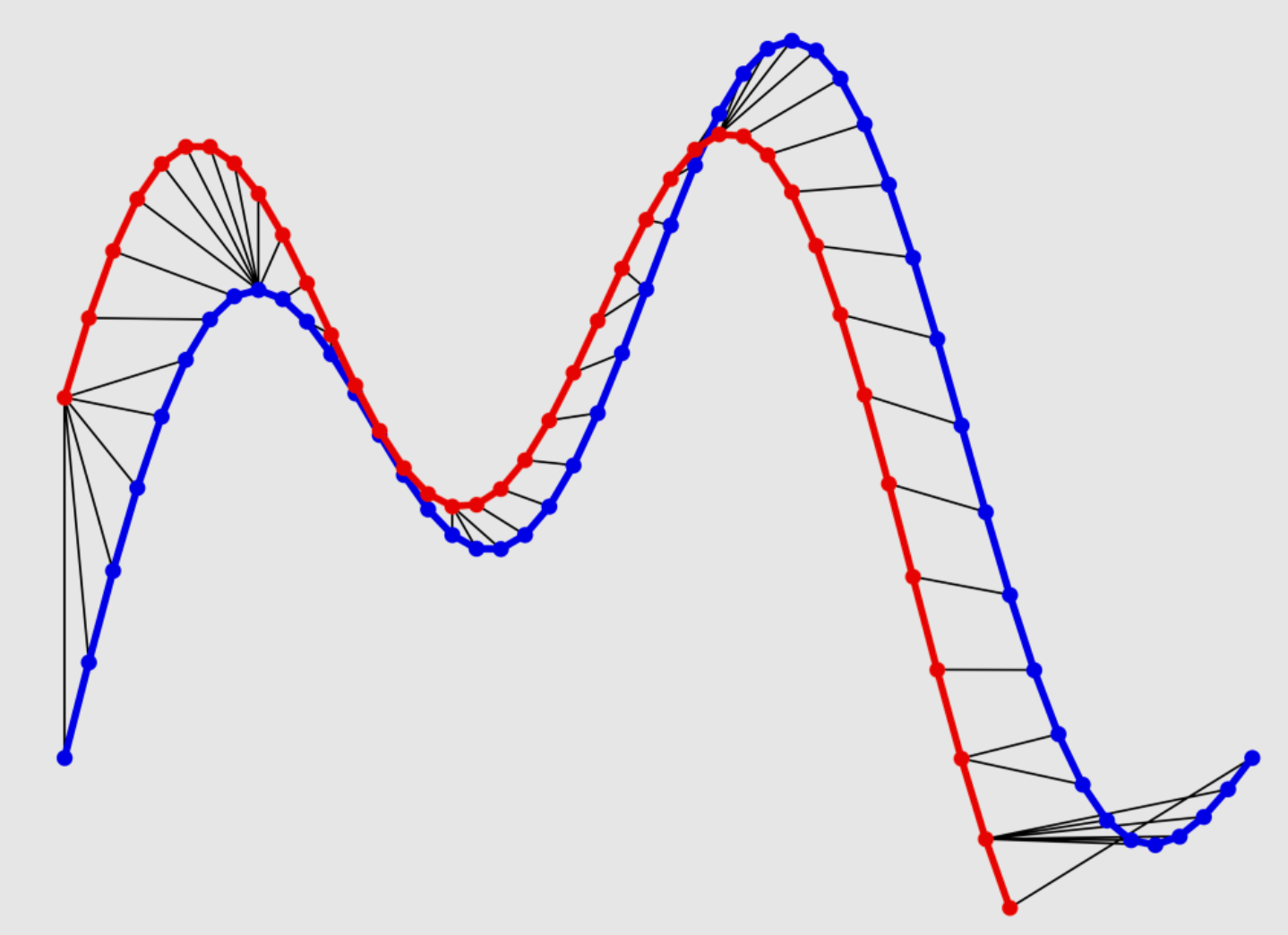

Dynamic Time Warp (DTW)

We looked at examples of previous researchers tackling this challenge, achieving accuracies like 99.40% (Rwigema et al., 2019) and 96.70% (Celebi et al., 2013). The most common approach is to use the algorithm Dynamic Time Warp.

This algorithm aims to find the lowest distance-cost between two time series. The series are displaced to arrange them in such a way where an optimal match is made between them.

(https://ealizadeh.com/blog/introduction-to-dynamic-time-warping/)

From Essi (above link):

“Let’s assume we have two sequences like the following:

$$X = x_1, x_2, ... , x_i , ... , x_n$$

$$Y = y_1, y_2, ... , y_i , ... , y_n$$

The sequences \(X\) and \(Y\) can be arranged to form an \(n-\)by\(-m\) grid, where each point \((i, j)\) is the alignment between \(x_i\) and \(y_j\)

A warping path \(W\) maps the elements of \(X\) and \(Y\) to minimise the distance between them. \(W\) is a sequence of grid points \((i, j)\)

The Optimal path to \((i_k, j_k)\) can be computer by:

$$ D_{min}(i_k, j_k) = \min_{i_{k-1}, j_{k-1}} D_{min}(i_{k-1}, j_{k-1})+d(i_k, j_k \: \lvert \: i_{k-1}, j_{k-1}) $$

Where \(d\) is a Euclidean distance \(d(i, j) = \lVert \mathbf{f_1(i) - f_2(j)} \lVert \)

Overall path cost: \(D = \Sigma_k \; d(i_k, j_k)^n \)

This algorithm effectively ensures that the data comprising two gestures can be accurately compared, without restricting the comparison to a strict time-axis. Furthermore, variations in amplitude and cycle length can be accounted for.

Real-Time Detection

To ensure that gestures can be detected without requiring too large a buffer, we empirically found that a buffer size of around 25-30 frames is sufficient. During runtime, the buffer is filled with the most recent frame fetched from the camera and the last {n} frames are processed using all the above steps.

An optimization step we take is to use FastDTW (Salvador & Chan, 2007), which approximates DTW in O(n) time complexity. The game profile determines which gestures are loaded for the game currently being played, and the distance between each of these gestures and the buffer motion is calculated. If it is below a certain threshold, it is added to the list of possible gesture options. The one with the lowest distance is returned and the buffer is flushed to allow for another gesture to be detected.

def detect_gesture(self):

processed = process_landmarks(self.point_history, include_landmarks=FOCUS_POINTS)

best_score = best_gesture = None

for gesture in self.gestures:

distances = []

num_points = 0

not_visible = False

for landmark_id, points in gesture.ratios.items():

count = 0

for coord in self.point_history[landmark_id]:

if coord[0] == 0 and coord[1] == 0:

count += 1

if count > BUFFER_SIZE // 2:

not_visible = True

break

else:

num_points += len(points)

distance, _ = fastdtw(processed[landmark_id], points, dist=euclidean)

distances.append(distance)

if not distances or not_visible:

continue

mean = sum(distances) / len(distances)

threshold = 0.8 + 0.02 * num_points

if mean < threshold:

if best_score is None or mean < best_score:

best_score = mean

best_gesture = gesture

if best_gesture:

best_gesture.activate()

self.clear_history()

References

- Celebi, S., Aydin, A. S., Temiz, T. T., & Arici, T. (2013). Gesture recognition using skeleton data with weighted dynamic time warping. VISAPP 2013 - Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications, 1, 620–625.

- Rwigema, J., Choi, H.-R., & Kim, T. (2019). A Differential Evolution Approach to Optimize Weights of Dynamic Time Warping for Multi-Sensor Based Gesture Recognition. Sensors, 19(5), 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19051007

- Salvador, S., & Chan, P. (2007). Toward accurate dynamic time warping in linear time and space. Intelligent Data Analysis, 11, 561–580. https://doi.org/10.3233/IDA-2007-11508

- Schneider, P., Memmesheimer, R., Kramer, I., & Paulus, D. (2019). Gesture Recognition in RGB Videos Using Human Body Keypoints and Dynamic Time Warping (pp. 281–293). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35699-6_22